By Barbara Ray

In rural Alabama, teachers in two K-12 schools 30 miles apart were working hard to support their students, but like in many rural communities, they were doing so alone, cut off from colleagues at other schools. Whether because of distance or poverty, the teachers at Francis Marion school in Marion, Ala., had very little interaction with their colleagues at Robert C. Hatch school in Uniontown.

Until that is, the National Writing Project’s professional development courses brought them together once a month for a day of learning and sharing.

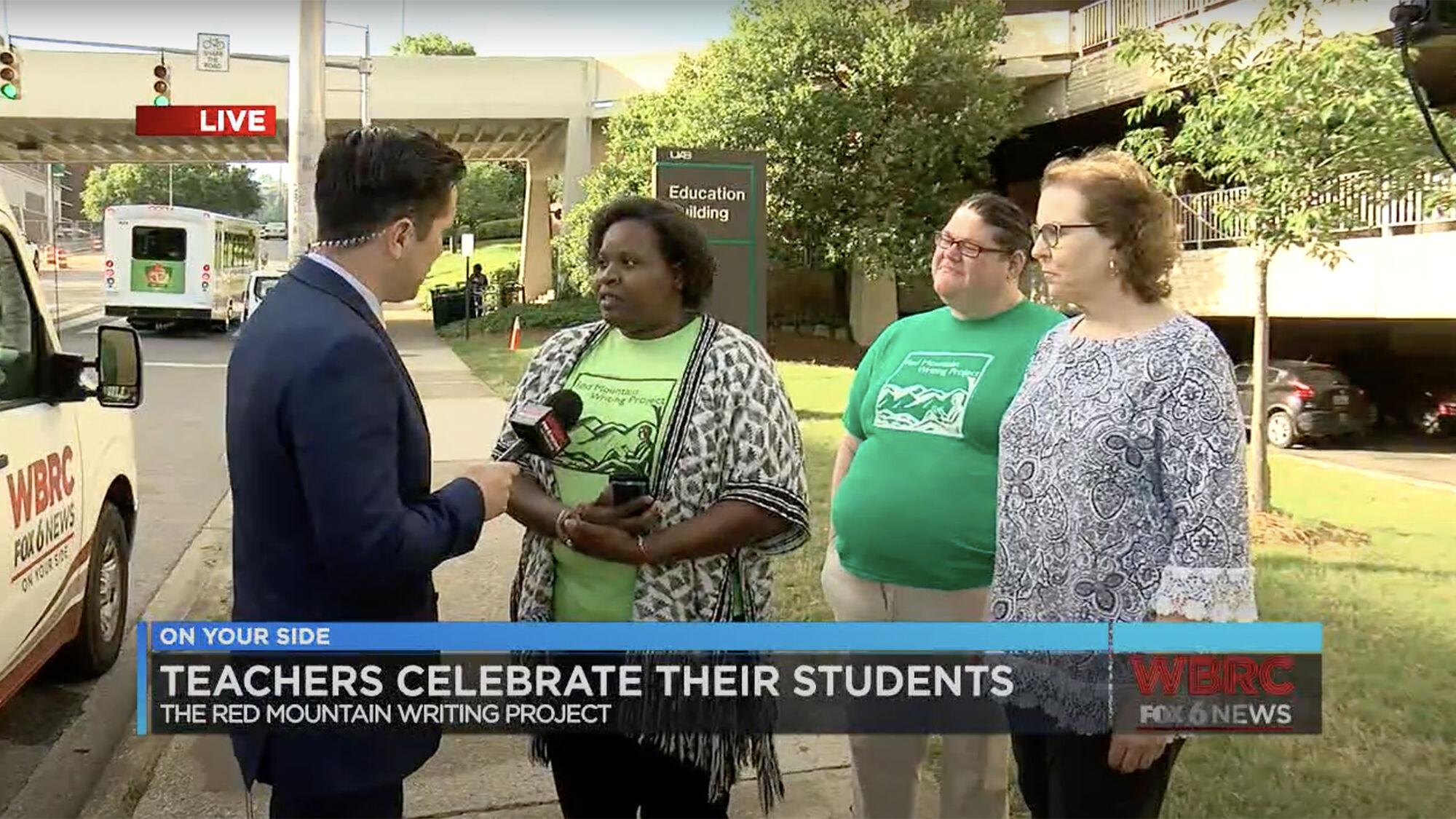

One morning each month, Jameka Thomas and her team at Red Mountain Writing Project would pile into their cars and drive the hour-and-a-half from Birmingham to Perry County. There, teachers from both schools would join together for a day of professional development in the art of argument—the civil kind.

The ambitious and successful National Writing Project course, College, Career, and Community Writers Program (C3WP), equips educators with the tools to help students form and argue a point using the written word, creating students who are civically engaged in the world “even if you disagree,” said Thomas, director of the Red Mountain Writing program.

As valuable as that is, the program came with an unexpected benefit, said Thomas. The convening would forge connections and foster a sense of community and trust that would help carry the teachers through difficult times, like the COVID-19 pandemic, which struck the two rural communities—some of the poorest in the state with nearly half the population living in poverty—toward the end of the 14-month professional development.

“One teacher had worked in his school for six years and had never experienced this type of community with other English teachers from other schools,” said Thomas.

That trust was evident one Saturday morning right before COVID hit. The principal of Marion Middle School pulled Thomas out of a session. A student had recently died after an asthma attack, she said, because there is only one ambulance for the entire county and they didn’t get there fast enough. The principal wanted her students to write about this tragedy as a way to spur action.

“The fact that the administrator saw us as a resource in order to get something done in her community says a lot,” said Thomas.

Thomas turned to NWP for a fast-response strategy session. The result was a plan to write about the devastating impact of health disparities—disparities that would underscore tragically with the pandemic. African Americans and those in poverty were much more likely to get sick and die from COVID-19 than others.

With schools shifting to remote learning during the pandemic, the professional development sessions shifted to Zoom and refocused on immediate needs. They surveyed teachers on how best NWP could help with new forms of teaching. They helped teachers set up podcasts and create their own library of texts to support students in arguing their points.

The teachers miss the collegiality but they are supporting each other through these trying times. They also carry with them a renewed sense of value, Thomas said. The NWP funding makes sure that simple things like breakfast are provided so teachers don’t have to worry about having to pay for those expenses. NWP pays for trips to conferences so teachers can enjoy themselves and learn without having to worry about the costs of a hotel room, said Thomas.

“We are really able to value teachers the way they are supposed to be valued. And NWP made that happen.”

That kind of relationship-building extends beyond the classroom. Kerry County is among the poorest in the state and also a food desert. To buy groceries, residents in Uniontown drove about 25 miles to the nearest grocery store. When their program peers learned that, they offered up their own community garden as an alternative.

“That was one of those moments that brought tears to my eyes,” said Thomas. “Seeing how they were meeting the needs of each other.”

When life returns to normal, Thomas and her team will take the program to Greene County, another rural Black community about two hours in the opposite direction to help another group of teachers build community.