This weekend a friend of mine introduced me to a writer who focuses on habits and decision making named James Clear. He isn’t exactly an education writer, but his posts are in many ways completely about education, as they are about how we learn, evolve, and view the world. There was one post in particular called Identity-Based Habits that sent me running to find my notebook for quotes like the following:

Your current behaviors are simply a reflection of your current identity. What you do now is a mirror image of the type of person you believe that you are (either consciously or subconsciously).

I think what grabbed me about Clear’s work is that I’ve been thinking a lot about the massive role identity plays in how students perform in our classes, and his wording so clearly encapsulated what I’d been noticing. The post’s introduction to me was also timely, as my interest in identity has further solidified over the last month as I’ve watched my Juniors go through the spring battery of standardized testing (for regular readers, that is where I’ve been over the last three weeks). While helping them prepare for these tests, I stood amazed by just how much their core beliefs about themselves seemed to control every aspect of how they approached these tests. The students who identified themselves as a bad writers and expected to fail avoided studying at all costs. The message was clear: They knew they were bad, so what was the point and why spend time thinking about something they will never be good at? On the other side, students who identified as strong writers came into my classroom at all hours of the day with stacks of practice essays, highlighted practice questions, and dozens of clarifying questions concerning the most minor rhetorical or mechanical details. They knew that they were good writers, and they were going to ensure the number the test spit out would match their skills.

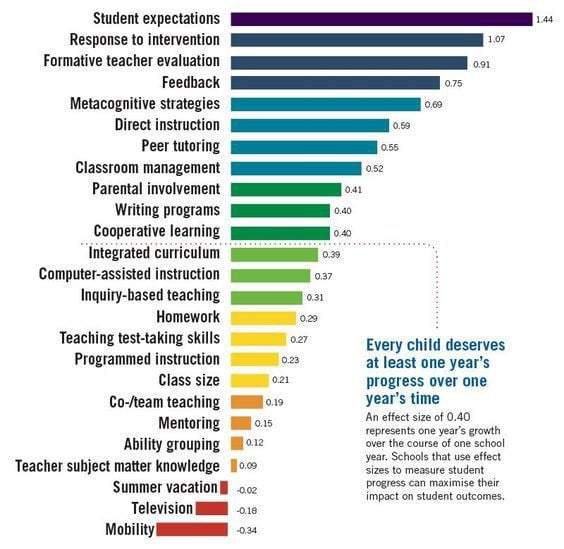

I recently came across a researcher named John Hattie who reads every piece of evidence possible concerning education and ranks factors that influence student growth in the classroom. While each year the rankings shift according to new data, the top spot has been clearly occupied by “student expectations” — which is essentially a synonym for student identity — for nearly a decade straight. And after the last month I am even more completely convinced he is right.

Some of John Hattie’s Effect Sizes

I’ve written previously about how a large number of students enter my classroom identifying as bad writers or not even writers at all and how I strive to improve their identities by offering thoughtful praise and building narratives of progress that reframe their journey as writers in a positive light. But I want to go further because during my last round of responding to student papers, I was struck by a realization: If one thinks about it, teachers are the only serious audience most students have ever had for their writing. Sure, a few will be writers outside of class and some might have parents or peers occasionally help with little things, but for the vast majority of students, for their entire lives, teachers have probably been the only ones who have deeply and directly responded to their writing, making teacher responses more than important to student writing abilities; for many students, how their teachers have responded to their writing is likely at the geographic center of how they see themselves as writers.

When considering the massive influence a students’ identity has on their learning and the core role teachers play in how most students view their writing, it is essential that we do everything possible to make sure that our responses cultivate positive writing identities for our students. Luckily, some of our best teachers have long recognized the awesome power identities have and the awesome power teachers have to impact student identities. Here are some of the best suggestions that I always strive to keep in mind to make sure that I am helping my students to build writing identities that are positive and growth oriented, as opposed to negative and closed off:

- In Teaching Adolescent Writers, Kelly Gallagher’s first commandment for building successful young writers is: “Remember that all writers, especially young writers, are fragile. They break easily. Don’t pound them by pouncing on every error. Nurture them by keeping the focus narrow and attainable.” I am a gardener, and so Gallagher’s combination of fragility and nurturing struck a chord with me. When I first look at any paper, I strive to remember this line and use it as my compass for approaching each student with the thoughtful, calculated care that I give to my seedlings when they are transplanted in the spring.

- In Embarrassment, Tom Newkirk references a quote from Plato where he compares writing to sending one’s child into the world “unprotected from misunderstanding and criticism.” In conversations we can clarify, hedge, justify, and otherwise revise our message based on its reaction, but this is not the case in writing for both the student who writes the piece and the teacher who writes comments on it. This is why I always do writing conferences (more on how to do that with tons of students here). No matter how clear and kind I think I was in my feedback, I always have a number of students who are confused, upset, or both confused and upset by my responses; conferences, beyond all of the other benefits they bestow, are my way to read the student to ensure that my messages are received correctly and work towards building up a student’s writing identity instead of knocking it down.

- In No More Fake Reading, Berit Gordon says that “Teens are grateful to have an adult who listens. And they’re shocked when an adult doesn’t come with all the answers or lecture on what to do.” I’ve already talked about how essential it is to make it clear that you are listening to students, but what I love about this quote is how it also highlights the importance of not offering answers at times. As teachers it can feel like our job to always have the answer, but by opening space for students to fill in some answers too, you are both making them work (which will help them learn) and showing that you trust that they are enough of a writer to do it right.

- In Helping Children Succeed, Paul Tough argues that what makes successful parenting coaches is that they, “don’t get hung up on which specific nursery rhymes and peekaboo techniques parents use with their infants; they know that what matters, in general, is warm, responsive, face-to-face-parenting…That parenting approach, however it is carried out, conveys to infants some deep, even transcendent messages about belonging, security, stability, and their place in the world.” He then makes the claim that these principles also all hold true for our classrooms too and that teachers, both consciously and unconsciously, constantly send explicit, implicit, or even subliminal messages about how students fit in the classroom. I’ve found this to absolutely be the case. Students can generally feel how we feel about them, and in the context of writing that often means they can feel whether or not we think they are a good writer. With this in mind, I strive to approach each paper with the mindset that this writer, like every other student in the class, has strengths and areas in need of growth. This might seem like a small shift, but I’ve found occupying this mindset usually makes a major impact in how I respond, especially in regards to the students who do have a lot of struggles and generally feel as though teachers don’t like their work.

In the end, the idea of using our feedback to both teach the students content and to cultivate the students’ writing identities may seem like a heavy lift. I get that, as teaching content in the margins is already hard enough and identity is abstract, largely unconscious, and not an easy thing to shift. But it is worth thinking about it, as identity is incredibly powerful stuff. Further, in the end there are actually only four identified factors associated with students developing what are considered positive mindsets. For those, I will end by turning it back over to Paul Tough. He argues that students will have positive mindsets that are set up for success if they believe the following:

- I belong in this academic community.

- My ability and competence grow with my effort.

- I can succeed at this.

- This work has value for me.

Or put another way, get students to believe they belong, can do it, and should do it, and you have a very good chance to change their writing forever!

. . .

Matthew M. Johnson has taught every grade 7–12, written a book for new teachers, contributes to Edutopia and Principal Leadership magazine, and taught in both private and public schools. He is currently working on a book for Corwin on writing instruction and regularly delivers professional development and keynotes across the country.