If you are a reader of The New York Times — or even if you have your #nwp alerts on — you probably saw the article “Why Kids Can’t Write” that names the National Writing Project (NWP) and features a visit with a thoughtful Teacher-Consultant Meredith Wanzer and the Co-Director Kathleen Sokolowski of the Long Island Writing Project.

I saw the article in its early digital version, pointed out to me by Google Alerts. When the famously bulky Sunday Times arrived, we saw ourselves on the front page of the Education section. So that’s something: a positive mention in The New York Times along with a call for more sustained attention to writing as an essential skill for college, career, and, we might add, for life. The piece also pointed to the importance of teachers becoming writers themselves, actually doing the craft that they will teach. This is a deep tenet of the NWP where we have seen how our own attitudes toward writing influences our teaching in significant ways.

Much to appreciate, we thought, but something not quite right, too. By its conclusion, the article advanced some older, erroneous framing ideas about the teaching of writing, frames that recall an earlier era of a ‘process vs. skills’ war in literacy education. That narrative of a war came from the Whole Language vs. Phonics controversies that absorbed the policy-makers who would legislate approaches to reading instruction in the 1990s, reaching a kind of fever pitch breaking point around the publication of the Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching Children to Read by the National Institutes of Health in 2000.

The “Wars” analogy may have described arguments among scholars, funders, and policy-makers, but it barely described classroom practice in the reading — an area that occupies significant instructional time in elementary school classrooms. “Wars” metaphors certainly never captured the teaching of writing, an area of the curriculum that occupied almost no classroom time. Yet arguments about a ‘war of approaches’ still sometimes cast NWP and similar organizations as advocates for a kind of laissez faire approach to the teaching of writing that assumed if young people did enough free writing or journal-keeping, they would somehow teach themselves to write.

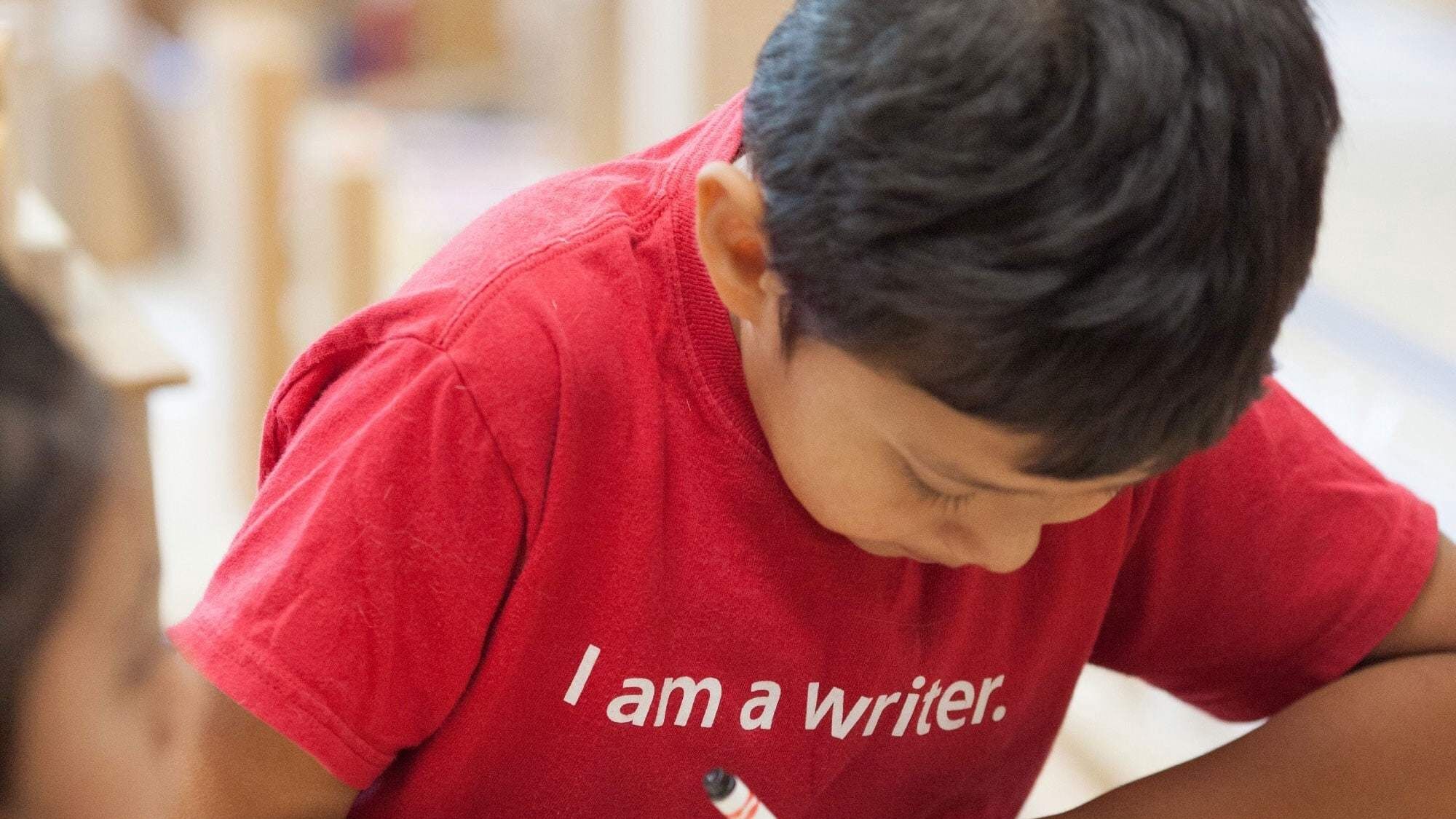

I remember that era well. I was a teacher and teacher-consultant at that time, and I fully remember the careful attention teachers of writing gave to all the dimensions of writing, including matters of style and mechanics that often fell into the “skills” side of the process vs. skills argument. This was true for those of us who worked with young people who came to those skills easily as well as those whose young people found writing challenging or who struggled with academic English. This was true when we worked on poetry or memoir, as is referenced in the article, and when we worked on writing in science or social studies, in research or argumentation. What was new and different in the emerging approaches to the teaching of writing wasn’t that we weren’t teaching the mechanics of written language — it was that we weren’t only teaching the mechanics. We were, above all, inviting our students to actually write.

In truth, the process vs. skills argument has long since quieted down. The ‘blended approach’ the article advocates is one that most teachers subscribe to. We want young people to attempt meaningful and ambitious writing where they search for, work at, deeply consider, and ultimately express something that is important to them to an audience that matters. That “importance” is a powerful motivator for doing the hard work of revising and editing, polishing, and publishing, and ultimately caring enough to get the mechanics right. That sense of an audience that matters, one that will take what you write seriously so you had better take your writing seriously too, is the context in which skills, process, and the vital substance of a piece of writing are best learned and best taught. It takes a lot of such writing to make a writer.

We Know So Much More Today

Years of research confirm the article’s assertion that most teachers have little pre-service or in-service training on how to teach writing and that students do little of any depth or complexity. In many schools, the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) era had a significant negative impact on the amount of writing in schools. In 2013, NWP co-published Arthur Applebee and Judith Langer’s Writing Instruction that Works: Proven Methods for Middle and High School Classrooms, detailing how even decades after their earlier research the writing required in most schools was minimal, shallow, and sporadic. This minimal attention over many years of schooling is a more likely cause of young people’s performance in writing than any seeming debates over methodology.

In the years since the early research that launched what came to be called ‘the process approach’, the field has accumulated a substantial research-base. Specific to NWP’s own work, in 2016 SRI Education conducted one of the largest randomized control studies of writing and professional development in its evaluation of our College-Ready Writers Program (CRWP). This evaluation involved 44 high-needs school districts in 10 states and found that our professional development model had a positive and statistically significant impact on all four attributes of student argument writing — content, structure, stance, and conventions — as measured by the Analytic Writing Continuum for Source-based Argument Writing. CRWP is a good example of how many teachers think about writing today in that it focuses on source-based writing — reading multiple and conflicting texts on civic topics, determining an argument in an area of emerging knowledge, and writing an effective argument. Montana Writing Project teacher Casey Olsen describes how this work impacts his students in an EdWeek blog.

Over the course of a school year with CRWP, one would see teachers doing everything from using informal writing to gather material and start to put together a position on a topic, to direct instruction in determining the credibility of a source or developing a line of reasoning, to practice with the elements of grammar and mechanics necessary to edit a piece of writing or proofread for errors. Students may be arguing real issues and policies in the civic life of their community for real audiences and with real outcomes. It is an area of writing that is quite different from the work with poetry that was observed in the New York Times’ visit to the Long Island Writing Project (LIWP), but that work with poetry is part of the picture too and no less important in developing a fully rounded set of expressive tools. Set alongside each other, CRWP and the LIWP poetry work represent the value that NWP places on engaging young people and teachers in a broad range of writing.

The SRI evaluation was funded by the U.S. Department of Education through an Investing in Innovation (i3) competitive grant the NWP received in 2013. As local NWP sites work to expand the program to new districts and invite new teachers into a relationship with writing, we see continuing evidence of a number of the problems named in the New York Times piece: little (or no) time devoted to writing, teachers who have never had preparation in the teaching of writing, and teachers whose experience with writing was so negative that they shy away from it in the classroom. Most of our nation’s teachers have only taught under the more restrictive focus of NCLB where writing was much devalued. To return writing to the curriculum will require that we embrace writing as an essential part of the curriculum across subjects and throughout schooling.

There’s Still So Much Work To Do

And so, how wonderful that writing was mentioned in The New York Times, and on the cover of the Education section no less. But rather than debate the merits of one teaching strategy over another, the real need is to advocate for writing and the teaching of writing itself. Those many teachers who have had little or no opportunity to learn about the teaching of writing may have even less if state and federal budgets continue to cut funding for professional development. The President’s FY 2018 budget proposes to cut the Department of Education by 13% — including eliminating Title II.a, the largest funding stream that each state receives to support the professional development of teachers.

Writing matters, and so we want the whole package: the skills, the substance, the creative and the critical, and ultimately the engagement with the power writing holds to unlock learning, action, and opportunity. Ultimately, we are pleased that The New York Times thinks that writing matters too.

. . .

Elyse Eidman-Aadahl is the Executive Director, National Writing Project